501 E Craven Ave

Lacy Lakeview, TX 76705

Phone: (254) 799-2458

History

Lacy Lakeview is a proud community with a rich history.

Neil McLennan (1787-1867)

Neil McLennan was born on Sept. 2, 1787, in the Highlands of Scotland and immigrated to America with his family in 1801, settling in North Carolina. In 1816, he moved to the Spanish province of Florida, where he engaged in farming with his brothers, John and Laughlin. On Jan. 14, 1835, these three families embarked on a small schooner for Texas, arriving at the mouth of the Brazos River, up which they proceeded as far as Fort Bend where their vessel was wrecked by striking a submerged snag. They then proceeded overland to Pond Creek in present Falls County, where they settled.

The following winter Indians killed Laughlin McLennan and several members of his family and captured his children. The other families moved down to Nashville-on-the-Brazos for security. John McLennan was killed by Indians in 1838. Neil McLennan was a member of George B. Erath’s Milam County “Mounted Volunteers,” engaged in Indian scouting and warfare in 1839,when he first saw the territory that was to become McLennan County. He stopped to survey land and in 1845 returned to the South Bosque River, built a house and planted crops, thus becoming the first white settler in the Waco area, west of the Brazos River.

He lived here until his death in 1867. When the new county around Waco was organized in 1850 it was appropriately named McLennan in his honor.

Jacob Walker (1805-1836)

Jacob Walker was born in Columbia, Tenn. in May 1805. He later moved to Maury County, Tenn. Sam Houston was his cousin, and one of his brothers was the famous mountain man, Joseph R. Walker. who was one of the first guides to California. Joseph Walker has rivers, lakes and mountains named for him. Jacob had another brother named Jack Walker. and his father’s name was John Walker.

Jacob Walker moved to Louisiana and met Sarah Ann Vauchere. They were married in November 1827. They had two children while in Louisiana where Jacob had a farm. He then moved to Nacogdoches, Texas were they had five more children.

In 1835, Sam Houston stopped in Nacogdoches and persuaded his cousin to join the army because they were giving land to the soldiers. Jacob’s first battle was the storming and capture of Bexar, Dec. 5-10, 1835. The siege of Bexar brought Santa Anna as the head of his army to retake San Antonio and Texas. Men indecisive about their future as Mexican citizens or Texans were moved irrevocably to independence.

After the Siege of Bexar, Walker remained as a member of Carey’s artillery company carrying out his duties as a gunner during the battle of the Alamo.

According to Susanna Dickinson, Walker was the last man to die at the Alamo. He plugged his cannon with scraps of cast iron and broken pieces of chain and fired at the Mexican soldiers. A Mexican officer trained a force of muskets on them. Walker, who had remained by his cannon until his wounds kept him from firing, leaped from the ramp and dashed to the side of Mrs. Dickinson in one of the chapel side rooms. Within moments, the Mexican soldiers broke through the old doors. The bloody fighting was fierce but brief. It is believed that Walker was attempting to ignite the main powder magazine that would have blown the Alamo to pieces, but because of his injuries crawled to Mrs. Dickinson and begged her to take a message to his wife, Anna. He then turned to face the Mexican hordes. Mrs. Dickinson said the Mexican soldiers shot and bayoneted him to death as she looked on. The soldiers pitched him around on bayonets, as they would a bail of hay. She was one of a few who was spared during the massacre. Walker died on March 6, 1836.

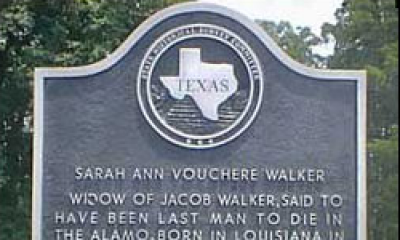

Sarah Ann Vauchere Walker (1811-1899)

Born Sarah Ann Vauchere on April 16, 1811 in Louisiana, this future pioneer was the youngest child of the French aristocrat Joseph Vauchere. At 16, she married Louisiana landowner Jacob Walker and two years later moved to East Texas with him. Sarah had seven children–three girls and four boys in the nine years before the Texas Revolution. In 1836, Jacob Walker left his family to defend the Alamo and was, according to one of the survivors, Suzanna Dickinson, the last man to die there. Dickinson said that Jacob had spoken to her several times during the siege “with anxious tenderness” about his wife and his four sons, and at the end she “saw four Mexicans toss him up in the air as you would a bundle of fodder ) with their bayonets, and then shot him.” In the dark days when General Sam Houston and a rag-tag band of volunteers were being hectored northward by the forces of Santa Anna, it seemed that any additional difficulty might finish the revolution altogether. The widowed Sarah achieved fame herself when she answered the call for a volunteer at a patriots meeting held in Nacogdoches. The patriots wanted General Sam Houston warned that the Cherokees had been incited by the Mexicans to ambush the Texas army from the rear as it retreated from the forces of General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna. A tiny woman only four feet eight inches tall and twenty-five years old, Sarah beleived that she could pass through enemy lines disguised as a boy and set off on horseback. She rode for day across a sparsely settled area where hostile Indians hunted, Mexican solders marched, and many other dangers for a lone woman existed. Three hundred miles later, Sarah reached the town of Gonzales, located Houston and his army, and gave him the intelligence that allowed his army to avoid the Cherokees.

Less than a year after her husbands death, Sarah married his cousin Jim Bob Walker. Being widowed on the frontier was a common female experience and, because the majority of the population was male, quickly remarrying was an established custom.

For the valiant sacrifice made by her husband (Jacob Walker), a grateful Republic of Texas issued to her Headright Certificate Number One, deeding to her “a league and a labor” (about 4,416 acres). The certificate was signed by President David G. Burnet, who held the office of President from March 16, 1836 to Oct. 22, 1836. The certificate did not locate the grant of land until Feb. 1, 1841. Col. Leonard William’s, first Indian Commissioner of Texas, located the grant of land for her. The Walker Grant was east of the Brazos River, beginning at a point slightly north of the mouth of the Bosque River and extending past White Rock Creek. The property also stretched east beyond Tehuacana Creek.

Sarah planned to move there from Nacogdoches after the birth of her eighth child but delayed because she quickly became pregnant again. The move of the household, slaves and stock began during this ninth and final pregnancy. Sarah was determined to have the birth on the Brazos. The baby came earlier, however, and was delivered “somewhere on the Sabine Trail.” Before Sarah could establish her family on the new land, her second husband died. The 1850 Census listed her as “family head, occupation farmer.” It was not unusual for survivors in the West to marry three or four times, but Sarah chose not to remarry again.

With considerable temerity, Sarah assumed responsibility for settling her newborn infant, a one-year-old, and her seven older children in the wilderness of Central Texas. She built her log cabin on high ground facing the Brazos River and enjoyed the benefits of fresh water from nearby springs, fertile black soil and Indian peach trees. With many people looking for land, Sarah lived by selling off parcels of her land grant. Early documents record that she and four of her children sold 130 acres on the Brazos for $3,660 and that she leased some of her land and rode horseback to collect rent from her tenants.

Sarah Walker not only endured, she prospered and replaced her cabin with a two-story Greek Revival structure with large porches in the front and back. For years, hers was the only house north of the Waco Indian Village on the Military Road, and travelers frequently stopped to drink from the cool spring waters and rest their horses. Indians came by also, but did not attack, perhaps because Sarah gave them gifts of food. The two oldest Walker daughters married and left home soon after they moved to the Brazos. Two of the sons and one daughter died before 1855. A third son, John, moved into a small cabin away from the family house and lived a secluded life. The 1870 Census listed him as male, 38, with no property of his own, and “an idiot whose privilege to vote had been discontinued.” The other three children lived on the Walker plantation until the Civil War, when another son was killed in the Battle of Bull Run and the youngest daughter married.

Sarah Ann Walker continued alone while the Military Road became the old Dallas Highway and the family cemetery behind her house filled with her children. As she aged, she became an increasingly devout Catholic and worshiped regularly at home. As hardy a pioneer as the West had, Sarah witnessed the extension of the frontier into Texas, participated in the Texas Revolution, saw Waco Village born, and almost lived to see the turn of the 20th Century. She died peacefully at home on Dec. 10, 1899, at 88. She was buried in the family cemetery behind her house and what is now known as the Walker-Stanfield Cemetery.

Stanfield-Walker Cemetery

The Stanfield-Walker Cemetery is in Lacy Lakeview, Texas, on the east side of North Lacy Drive on U.S. Hwy 77-81, between Stanfield Drive and Ave. C . In 1844, when Sarah Walker settled on her Headright Certificate Number One, land that was given to her for compensation for the death of her husband, Jacob Walker, who was reported to be the last man killed in the Battle of the Alamo. The cemetery is known as Stanfield-Walker Cemetery and was originally the cemetery for Sarah Walker’s family. Sarah Walker was born on April 16, 1811 in Mississippi and died on Dec. 10, 1899. During the years, not only have the family members of the Walker family been buried there, but also it is reported that cowboys who died moving cattle up the Chisholm Trail, which ran through the Walker land, also were buried there.

Walker’s family cemetery became the Stanfield-Walker Cemetery when Walker’s daughter, Margaret, married Francis Stanfield. Margaret Walker was born on July 18, 1832 and died on March 8, 1923. Francis Stanfield was born in 1847 and died in 1869. He was probably killed by outlaws, as the LaVega grant to the south of the Jacob Walker grant was a “no man’s land” and a notorious hideout for criminals. Family members from both the Walker and Stanfield families are buried in the cemetery.

Jim Bob Walker’s grave is the oldest grave in the cemetery and is walled in with native sandstone blocks. The marker shows he died in 1850. Two unmarked stones, very old native sandstone, probably mark graves of some of the “Walker” descendants. Ada Stanfield was the first Stanfield to be buried in the Stanfield-Walker Cemetery. She was the daughter of Margaret Walker Stanfield. Ada Stanfield was born on Jan. 23, 1875 and died on July 23, 1876 .

Chisholm Trail

During the past century, the Chisholm Trail has been all but forgotten. Houses, trees and golf courses stand where once it was as clear as an interstate highway. Some of it is still open pasture, some of it has been plowed countless times to plant wheat, cotton or other agricultural products. Barbed wire fences have shredded what remains of the trail.

Because Texas is were the longhorns once roamed, this is where the trials began. The Chisholm Trail was named after Jesse Chisholm, a Cherokee Native American. He was a trader, interpreter, guide and businessman. He had already traveled the trail numerous times, hauling freight in wagons that were pulled by oxen from Kansas to stock his trading post, or rather trading posts that extended to the Canadian River. It is said that he was the first to create a chain of convenience stores.

In the early years, Jesse Chisholm in his bartering with the Indians, was principally interested in securing furs and buffalo robes from the Indians but had to accept some cattle for his goods. When he had gathered several hundred head of cattle, he would drive them to Fort Gibson.

Texas Longhorns were descendants of cattle brought over by the Spanish. Whatever the genetic background, longhorns were left alone to survive in the wilds of northern New Mexico and southern Texas while the men went away to fight each other in the Civil War. Nature converted the once domesticated animal into a lean and hardy breed, fully capable of defending itself against most predators with its long horns and sharp hooves. The end result was a breed of cattle resistant also to disease and drought and flourished until they numbered in the millions.

At the end of the War Between the States, longhorns were abundant. Thousand were killed for the tallow and hides. A good cowhide might bring as much as $3. Markets for the entire animal were rare, but if the cattlemen could get their product to Chicago, a market was waiting for them, paying as much as $35 to $40 a head. The cattlemen rounded up longhorns, cropped their ears, branded their hides and drove them north across the Indian Nations into Kansas. The trip was not easy, and the cattlemen had to deal with unhappy farmers and ranchers, prohibitive laws and uncooperative weather. When the cattlemen arrived at Kansas or Missouri with their herds, they had to deal with roving bands of ex-soldiers who called themselves Jayhawkers or red-legs and who enjoyed murdering Texans.

The first year that the Chisholm Trail was used, an estimated 260,000 head of cattle were driven towards Kansas or Missouri, but only about half reached their destinations.

The Chisholm Trail extends from Brownsville at the southern most point of Texas and extends north through Texas, Oklahoma and ends in Kansas. The trail ended in Kansas at Dodge City, Hays, Ellsworth or Abilene.

The Chisholm Trail also came through Waco, Texas on its way north. Cattlemen stopped along the Brazos river, and some camped on Sarah Walker’s plantation. The trail was abandoned in the 1880s as the land along the route was settled and cattle were shipped by rail. Somewhere along the way, without intending to do more than work for a hard day’s pay and board, they created the legend of the American cowboy.

First Schools

Josiah Frost had a 320-acre farm in 1860 from which he donated a block of land on which Frost School was erected. This was the first school in the community. It was a log cabin built on the plot of land now owned by the J.H. Montgomery family. The log cabin school was moved from its original site to a location across from the Dallas Highway in front of Alamo Steel Co. and later burned. A new school was erected where the log cabin had stood. This building was a one room school known as Frost School, and the school remained there until 1915-16 when a four-room, two-story red brick building was built in the Lakeview Addition on land donated by C.C. Shumway, a real estate broker, who developed the Addition. This school burned on twice in 1939. The school was rebuilt with aid from the WPA except for the gymnasium, which is still in use today. The school was replaced again in 1964.

Lakeview consolidated with Elm Mott in 1950-51. The school at Elm Mott, still in use, was built in 1920. The new school district was called Connally Consolidated School District. At that time, school was only taught to the 10th grade. Soon after consolidation, a high school was built on a 15-acre tract of land and named Connally High School. The area developed rapidly during the next few years, and another elementary school was built on the 15 acres and named Northcrest Elementary School in 1961. On April 8, 1974 a fire destroyed the high school except for the gymnasium and Home Economics building. Local churches were used for class rooms until the school could be replaced. The school district bought additional land adjacent to the junior high complex that was built in 1965 to build a new Connally High School. This building was completed in 1976. The Connally Schools are highly recognized scholastically and academically.

Lacy Lakeview

Lacy was named for William David Lacy who initiated the growth of the farming community by selling lots near the present intersection of Craven Avenue and Interstate 35 during the 1880s. Lacy was on a mail route from Waco and became one of the interurban stops in the county. Lacy reported a population of 40 in 1930 and 1940 and 50 in 1947. It merged with the community of Lakeview to form the incorporated city of Lacy Lakeview in 1953.

Lakeview was named for its location near some spring-fed lakes and was built along the lines of the Texas Electric Railroad. In 1915, the Lakeview school replaced the Frost school at Lacy and was incorporated in 1927. The community was developed during and after World War II with the expansion of the James Connally Air Force Base. Lakeview reported three businesses and an estimated population of 70 in 1947.

Frank Mosely was elected the first mayor of the city in 1953. Two major residential districts in the area are the Connally Addition and the W. Morris Mosely Addition. The city’s present water system was founded by the J.C. Passmore family in 1949.

Spring Lake Country Club

One of the highlights of the past was the Spring Lake Country Club. It was an elegant resort for Waco’s wealthy to relax and entertain in the 1930s. It boasted a golf course, swimming pool, tennis courts and stables. The lakes were a favorite place for the members to visit their summer lodges built there.

The big club house was impressive and elegant with its dinning hall, big fireplaces, dressing rooms, locker rooms and the second floor ballroom. The club house stood imposing over the country side and silent lakes until it was condemned and torn down in about 1974. The Club had long since been closed. The Air Force had used the site just briefly in the 1950s as an officers club, but deterioration took over. The property has been developed into a subdivision with beautiful homes spotting the lovely terrain.

Things I remember most about my life in Lacy Lakeview By Alice Carey Hodge

(excerts from this book)

- Walking barefoot on the hot blacktop of Lacy Lane to Montgomery Store to charge a two cent banana on my parents account.

- The plays and amateur contest held in the school auditorium.

- The ice cream suppers on the lawn of the Methodist Church.

- Construction of the new school after it burned, complete with inside restrooms.

- Singing “Makes the Methodist love the Baptist” at revivals to the tune of “Old Time Religion”.

- Buying a pint of ice cream for 10 cents at the store near the school and eating all of it.

- Listening to Adolph Hitler’s speeches on the radio at school.

- Hearing Principal Grady Moore’s lectures about “diabolical devils,” as he called in unruly students and being instilled with his total patriotism and love of God and country.

- The day World War II was declared.

- The day the Lacy Lakeview boys left for war.

- Enjoying a camaraderie among neighbors unequaled in my lifetime.

Modern History

The Cities of Lacy Lakeview and Northcrest merged in 1998. The merger brought improved services and made the city a home rule city. The 2000 U.S. census shows the population to be 5,574. The city hired their first City Manager, Michael Nicoletti. This new leadership brought growth, increased pride in our community, vision into the future and improved customer service.